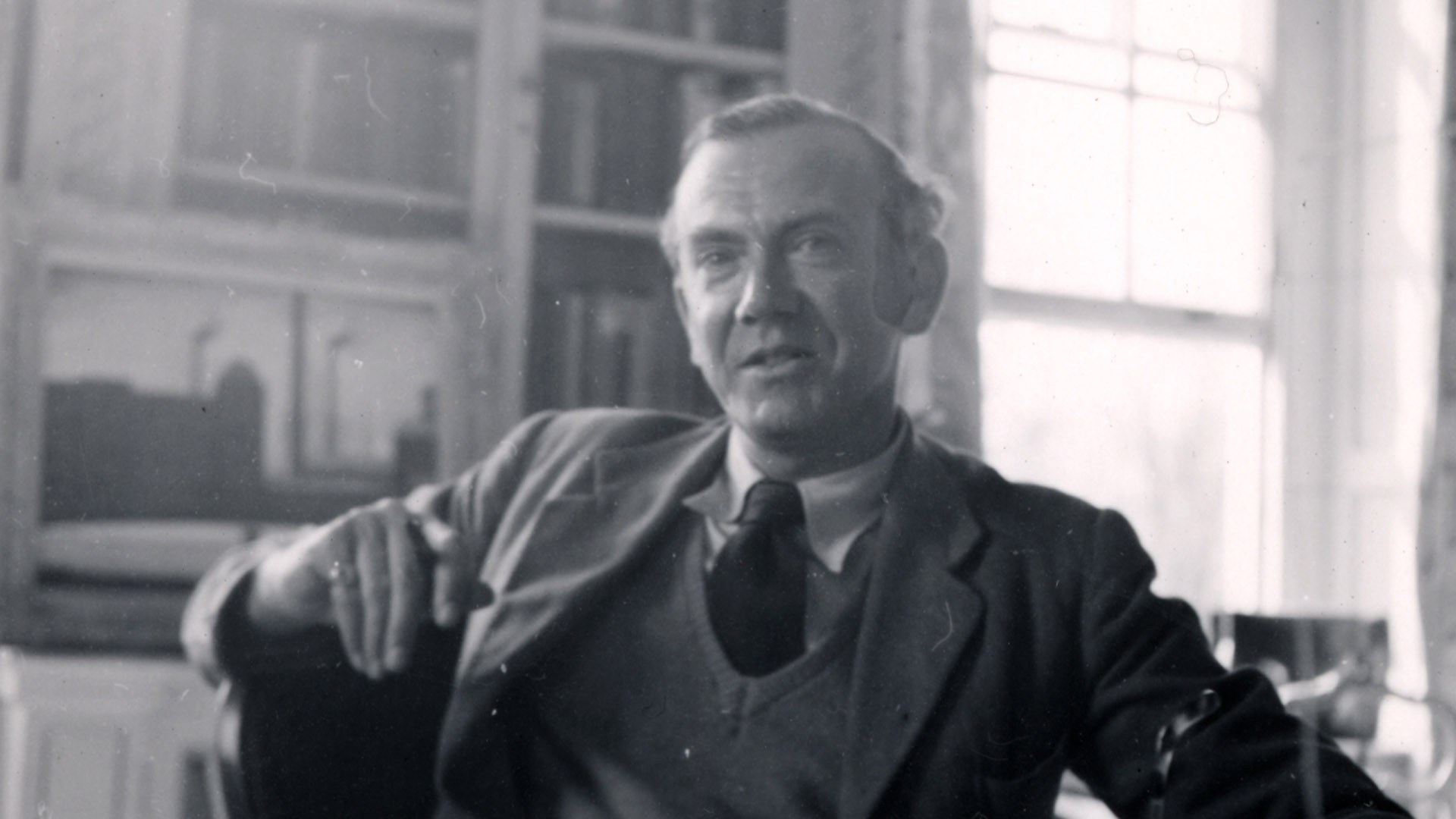

Barrel-organing by Graham Greene

Those who have barrel-organed in a hard December may be said to have graduated in that peculiarly classical profession whose gamut of tunes, in the form of a numbered dial, ranges from the Dead March in Saul to the Toreador’s Song. The latter was the gayest tune which my organ contained, and was intended, perhaps, to combat with its cheerful bludgeoning the searching rapier of the wind. It was the former’s velvet-hung pomp, however, which brouht in the pennies, until the organ, slipping from cold, clutching fingers, tumbled over and over down a steep Hertfordshire hill and came to rest at the bottom with all its bass notes broken. What seemed at first disaster and bankruptcy, for my friend Claud Cockburn and I were far from home with no money in our pockets but our scanty earnings, and with nothing to pawn but our elaborate and careful rags, proved a blessing. In the first street in which we played four separate elderly ladies gave us four separate sixpences on condition that we moved on to a neighbor’s house.

And in this connection it may be noted that in the country – I have no experience of London – the barrel-organist’s principal income is derived not from the rich but from the poor – the youths ‘walking out’ who wish to impress their companions with the measure of their charity and from women who bring their children to the door to listen to the music, bad music, perhaps, but music with a hint of a hot south – ‘des fruits, des fleurs, des feuilles et des branches’, These do not pay sixpence to the organist to go away, but pay him a penny for another tune. This is less profitable but more warming to the heart, and was very welcome on the three bitter December days during which I followed the profession and graduated, if not with the legendary motor-car, at least with a few pence profit.

Perhaps to begin with the organ was a little too polished in its performance to carry conviction of poverty, for it was only after disaster had marred its notes that we were admitted to the camaraderie of the profession. Among itinerant musicians there is a very real fellowship. Trundling the barrel-organ along a frozen lane, we met at the approach to a village one time a lean, drooping figure, curled round a forlorn pipe, who, passing, indicated, without staying his steps, the street in which the wealthiest harvest could be reaped; another time a fat, red fellow with a gramophone perched on a perambulator, who warned us between wet, pendulous lips of the presence of skinflints. Little do those who throw an organist sixpence in order to drive him away know that they are thus ensuring the arrival of a succession of similar players.

I do not know whether London is the Mecca of the barrel-organist, as it is of the more legitimate musician. Certainly during the winter it has great advantages over the country in the matter of lodgings. In London there is the crypt of St Martin between the common lodging-house and the Embankment; in the country there is little, as we proved to our cost, between the public house and frost-gnarled field.

Of all but one of the five towns in which I have barrel-organed I have nothing but pleasant memories. The exception should surely have been foremost in charity, since it was the birthplace of the English Pope, Nicholas Breakspear, friend of poor men and enemy of emperors. But in this town, because of our dirty faces and our rags, we were rejected at every inn. One inn, more friendly than the others, offered a stable for our organ, if we paid, but from his organ, as from his horse, a man should not be separated.

There seemed only to remain an iron-bound field, but here, after a few hours’ attempt at sleep, cramp knotted every muscle. Thence we made our way to a half-built house with a roof and floor, but only unlidded gaps for windows, through which the wind swept in a regular succession of chilling gusts. We woke again before dawn in the grip of cramp, and finally left the suspicious and uncharitable town for the comparative warmth of walking between high hedges, followed on our right hand by a spectrally coughing cow – and so trundled out of the profession for ever.

Listen! Outside the window a gradually growing tinkle of sound – small scented sugar-plums of brittle music dropping rapidly one by one into the blue dusk. Here is sixpence, organist. Do not go, but turn the handle of your dial and play another tune.

Graham Greene

The Times

27 December 1928